SEARCH THE COLLECTION

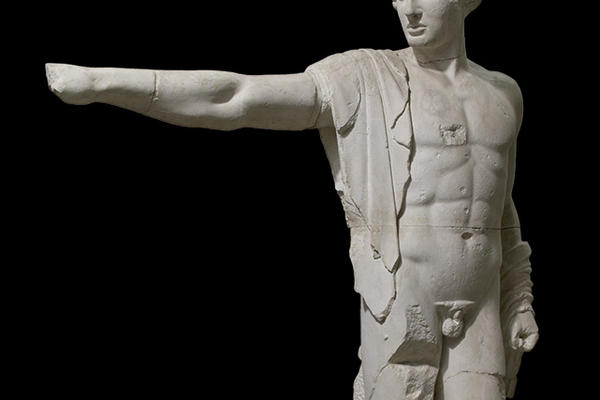

The Ashmolean's world-famous collections range from Egyptian mummies and classical scupture to Pre-Raphaelite paintings and contemporary art. We continually add to and update our online collection records.

COLLECTION THEMES

Myths and Legends of Crete

Myths and Legends of Crete

Japanese landscape prints

Japanese landscape prints

IN THE SPOTLIGHT

FLOWERS & INSECTS

FLOWERS & INSECTS

SCREEN WITH SPRING & SUMMER FLOWERS

SCREEN WITH SPRING & SUMMER FLOWERS

SPRING STORIES

SPRING STORIES

MORE TO EXPLORE

Collection highlights

Collection highlights

Introducing the collections

Introducing the collections

Stories